Zoological Aide Katie Schachtsick holds a long-handled back-scratcher and applies just the right amount of pressure as she rubs it across the black-and-white hide of endangered Malayan tapir Yuna.

It’s clear Yuna enjoys the attention – and the back rub – leaning into the scratcher and then moving her stout legs down, getting into a lying position. Who knew tapirs could sigh?

It’s all in a day’s work for zookeepers and veterinarians as they care for animals.

Back rubs for a mom-to-be

Yuna is several months pregnant. And when you want to get an ultrasound to see how the calf growing in her uterus is doing, you begin with a back scratch. Once relaxed enough, the 776-pound tapir – who can be skittish – will allow keepers to move even closer to her and Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium Associate Veterinarian Dr. Kadie Anderson to perform that ultrasound.

Her calf, fathered by Malayan tapir Baku, is due sometime this summer. The gestation period for their species is about 13 months, and veterinarians believe Yuna is somewhere around 60 percent of the way to giving birth. It’s tough to pinpoint a due date; the scientific community doesn’t have a lot of information on the length of tapir pregnancies, and tracking hormonal profiles in tapirs is difficult.

Already, keepers have seen and felt movement of the fetus through Yuna’s abdomen. When born, the calf can weigh as much as 22 pounds. He or she will look a bit like a brown-and-beige striped watermelon.

Acting Lead Staff Biologist Ryan Clifton enters Yuna’s bedroom in the Zoo’s Asian Forest Sanctuary and takes up a station near her head, rubbing her white middle with his bare hands, letting her know that all is well. The scratching session continues. Yuna is accustomed to this process; keepers trained both her and Baku to lie down and present their feet for care and allow ointment to be applied to rough patches on their skin.

A growing calf

Anderson hauls the ultrasound equipment – monitor, cords, wands, transducers and gel – into Yuna’s bedroom, then gets down to business. Asian Forest Sanctuary Staff Biologist Alicia Chapman stands by, carefully watching Yuna for any signs that she might startle and try to get up.

By now, the tapir is lying on her side, one back leg on the floor, another held in the air, creating a natural and convenient access for Anderson, who rubs gel on the tapir’s lower abdominal area, checks her equipment and then gently but firmly glides it across the area of Yuna’s uterus.

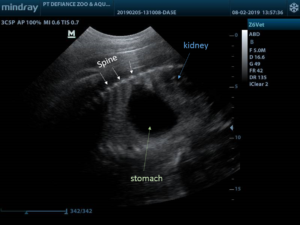

Zoo General Curator Dr. Karen Goodrowe, who holds a Ph.D., in reproductive physiology, squats behind Anderson, watching the procedure. Grainy black-and-white images soon appear on the ultrasound monitor. Anderson looks from the tapir to the screen and back again, moving the ultrasound probe as she does in an effort to get images of the developing fetus. Periodically she stops, points out portions of the calf’s anatomy such as its spine, than moves back to seek more pictures.

Anderson feels movement with her hand and on the ultrasound screen and detects what she declares to be a healthy heartbeat.

“I’m pleased,” she says as she packs up her equipment. “Yuna is a wonderful patient. We were able to identify the calf’s spine, ribs, stomach, heart and a kidney.”

After Anderson leaves Yuna’s bedroom, Clifton takes a cloth and gently wipes the ultrasound gel off of the tapir’s bulging abdominal area. “Good girl,” he says. “You are such a good girl.”

Watching over the pregnancy of an endangered Malayan tapir is just one of the many ways in which the Zoo’s experienced staff of keepers, veterinarians and veterinary technicians care for more than 14.400 animals in 527 species that live at the Zoo, Goodrowe said.

And a first for the Zoo

Happily, that includes overseeing the first Malayan tapir pregnancy in the Zoo’s 114-year-history.

Yuna didn’t need any changes to her already healthy, balanced diet of various fruits, vegetables, specially formulated grain, hay and browse, (no prenatal vitamins needed!), Anderson said. But she is receiving once-a-month ultrasounds.

Zoo guests may be able to see Yuna’s growing “baby bump” in one of the Asian Forest Sanctuary habitats once storm damage is cleared. Due to ongoing work in some of the habitat spaces, she will rotate on and off exhibit with other Asian Forest Sanctuary inhabitants.

The keepers who provide the tapirs’ daily care are excited.

“Pregnancies in Malayan tapirs are relatively rare in zoos,” said Senior Staff Biologist Telena Welsh, who has more than a little empathy for Yuna. Welsh is pregnant, too. “We’re delighted that Yuna and Baku are expecting,” she added. “We can’t wait for this birth.”