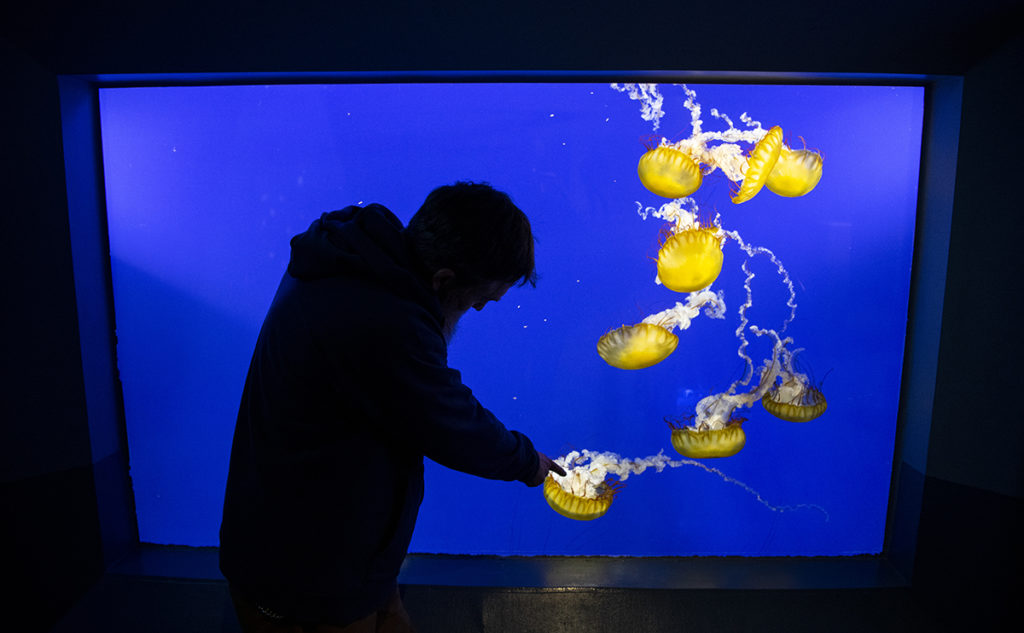

On the visitor side, the jellyfish gallery in the Pacific Seas Aquarium is a serene blue world of floating, pulsing forms. From eggcup to dinner-plate size, they hover in a kind of translucent eternity.

Behind a nearby door, however, is another world; a world of bubbling tanks, petri dishes and complicated piping. This is the world of Dr. Chad Widmer, aquarist at Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium and a world-renowned jellyfish expert. It’s a world of science, mystery and microscopic wonder – a world where the floating beauties outside are created.

Dr. Widmer’s Jelly Lab

With a long beard, bright eyes and fast speech peppered with scientific terminology and wry jokes, Widmer infuses his jelly lab with an infectious enthusiasm. He’s been breeding jellyfish for about 17 years now, and in fact wrote the book on it: “How to Keep Jellyfish in Aquariums: An Introductory Guide.” It’s still the standard textbook for jelly culture. And the astonishing thing is that Widmer creates many of those jelly babies through IVF – in vitro fertilization.

So how do jellyfish reproduce, exactly?

“I can show you all the steps, right here,” says Widmer, a gleam in his eye.

Swimming Larvae

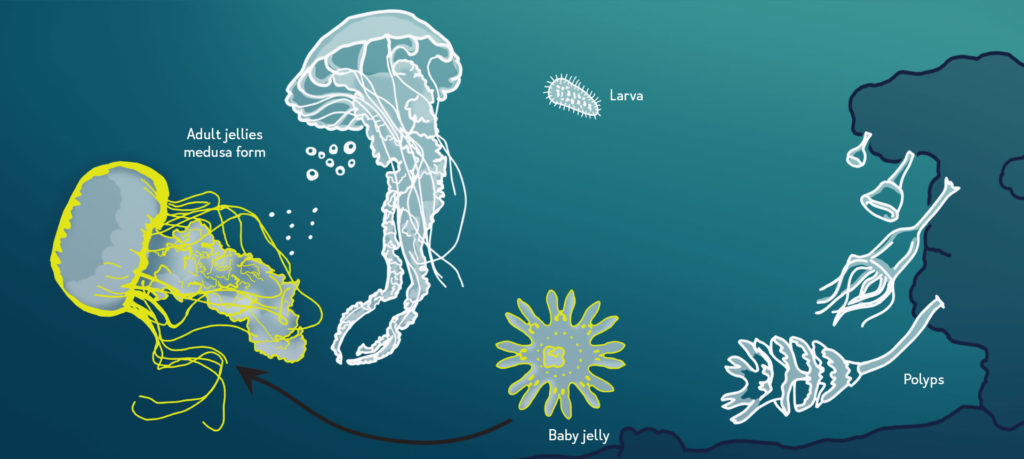

First comes spawning. Jellies may not have backbones or brains, but they’re sensitive to light, and at dawn or dusk males and females will send out sperm and eggs to fertilize in the water. Some females, like moon jellies, actually take up sperm through their mouths to fertilize internally.

Widmer rolls up a sleeve, reaches into a tank of pale moon jellies, each the size of a plate, and gently opens the four “lips” of one of the animals to demonstrate.

“Every species has a different life cycle, almost like a different animal,” he explains. “That’s why I’m still doing this – you learn things all the time.”

The fertilized eggs then develop into tiny swimming planulae larvae. Microscopic, they’re visible by the millions as whitish clumps drifting through the water.

Grabbing an eye-dropper, Widmer stirs up a mini-whirlpool in the moon jelly tank – “I learned this trick from watching phalaropes, those birds paddle their feet to bring up food” – and deftly sucks up a small cloud of larvae. He slips between tanks to a desk tucked into a corner of pipes and buckets, deposits the dropperful into a dish and sets it under a microscope.

As he focuses on the seemingly-empty dish, the computer screen brings up a world of black lumps, swimming madly.

“These are about four-tenths of a millimeter long and two-tenths wide,” he announces cheerfully.

Larvae to Polyp

In the wild, larvae drift and settle onto hard surfaces to become the next stage in a jelly’s life: a polyp. And here’s where Widmer is discovering things.

“Nobody really knows where polyps live in the ocean, except moon jellies, because we see them on the underside of docks out here in Puget Sound,” he says. “Maybe they’re on the ocean floor. But they like being on the underside of things like clam shells, so they’re more easily positioned to eat as food comes by. Here, look.”

In a corner of the tank, Widmer has set up what looks like a random collection of upside-down dishes. They’re actually polyp homes. Retrieving one, he flips it right side up and sets it under the microscope. Instantly, tiny polyps appear on the screen like many-fingered blobs, swaying.

“They’re about to eat,” Widmer says, pointing out tiny tentacles and mouths. “And if I move the dish, they react – see?”

Breaking Away

Polyps can stay this way for a long time, making clones of themselves in the form of buds. In his jelly lab, Widmer has a series of small tanks filled with polyp homes. He feeds them brine shrimp and rotifer zooplankton, and waits for them to make the next big jelly change – strobilation. Triggered by colder water temperatures (as in winter), the polyps will split into 10-15 Frisbee-like segments stacked in a tower, which then break off independently into the water as juvenile jellyfish.

They eventually mature into the medusa form we all know well: pulsing round body, long stinging tentacles and frilly oral “arms” that capture food and transfer it into that lippy mouth.

But while jellyfish do spawn in aquariums (long spaghetti strings of sperm were actually trailing from moon jellies in the globe that morning), they don’t always fertilize or reproduce.

Enter the science of IVF – taking male and female reproductive material from mature jellyfish, combining them in a glass (the original meaning of the Latin in vitro) or plastic dish, and mixing them up to fertilize and make larvae.

It’s a process Widmer is doing right now for the Japanese sea nettles – long, graceful creatures with a gold interior and flower-like orange pattern on their bells.

Science, care, fun

Around the rest of the lab, baby jellyfish swim slowly, growing big enough to move into the serene blue habitats on the visitor side. There are tiny Aurelia limbata – deep sea moon jellies just four millimetres across, and a very rare species in aquariums. There are bigger egg yolks, lions’ manes, Pacific sea nettles floating like distant stars. All get daily care and detailed attention from Widmer and the aquarist team, with task lists, feeding sheets and research projects outlined on whiteboards.

It’s not all serious science for Widmer. In his previous job at the Monterrey Bay Aquarium, he took a team from Pixar on a jelly tour and demonstrated how you could touch the tops of jellyfish without getting stung. It inspired the jelly-hopping scene in “Finding Nemo” as well as the nickname “Jelly-Man” – his own in-house moniker.

But for Widmer, the art and science of making baby jellies is just the tip of an iceberg of marine knowledge, one that he and other scientists are constantly discovering and sharing. It’s challenging, but it’s what keeps him and his team passionate about work every morning – plus the inherent beauty and mystery of this animal.

“There’s so much still to learn, so much meaningful work to be done on jellyfish,” he says. “It’s a very recent field.”