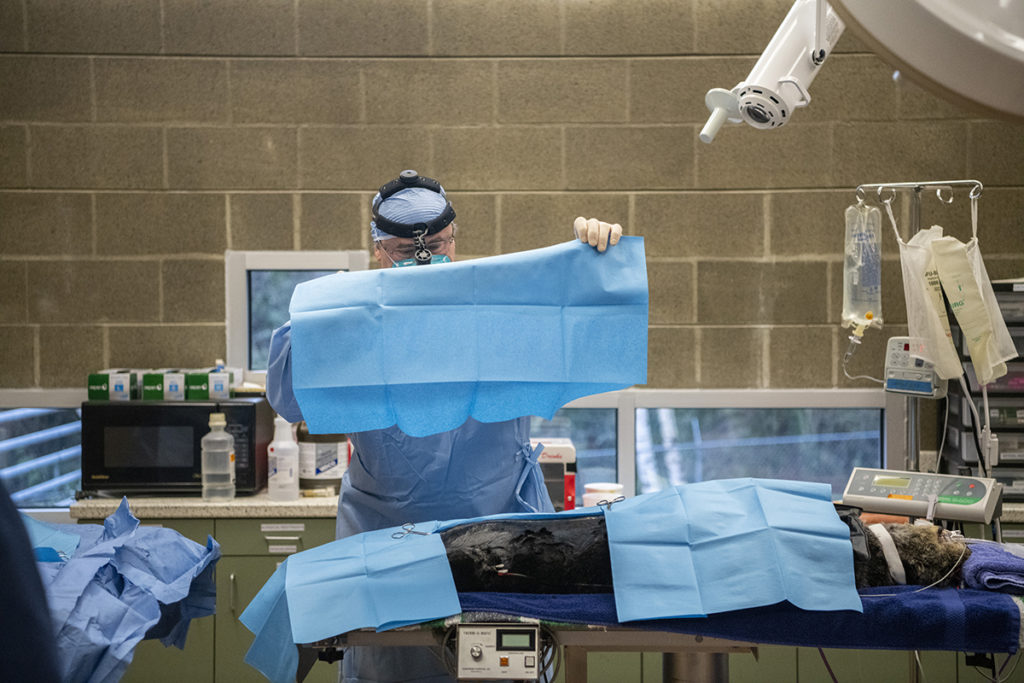

Dr. Karen Wolf, left, and Dr. Caitlin Hadfield prepare Sekiu for surgery.

NOTE: Graphic visual content further down the post.

On a cold winter’s morning at Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium Animal Health Care, head veterinarian Dr. Karen Wolf did an unusual thing during surgery: She put a fresh ice pack on her patient’s chest.

Sekiu the sea otter was in the operating room to have her ovaries and uterus removed, because a large tumor had developed.

But in addition to two veterinary surgeons, three veterinarians, two veterinary technicians and a zookeeper, Sekiu’s surgery needed a few other special protocols: partly because of Covid-19, partly her connection with Seattle Aquarium – and partly because sea otters have the densest fur on the planet.

“Is this the best way to comb?” asks Julie Lemon, one of the Zoo’s veterinary technicians. As she smears a brown goopy mixture of Betadine and lubricant over Sekiu’s thick black tummy fur, Dr. Caitlin Hadfield – veterinarian at Seattle Aquarium, where Sekiu was born – nods approval.

“You can’t shave around the incision site, as a sea otter’s fur is so important to help them regulate their temperature in the water,” explains Dr. Hadfield. “So we spread on this mixture and comb the fur away. This is the only species I know of where you would do that for surgery.”

It isn’t the only unusual surgery prep going on. Head veterinarian Dr. Karen Wolf double-checks Sekiu’s vital signs to make sure the ice pack is doing its job: Unlike most patients, sea otters are built for cold, and keeping them cool (rather than warm) was the goal. The January morning – one of the coldest of the year in Tacoma, Washington – had also been chosen for that reason, and all the doors were wide open.

But the doors were open for another reason also – minimizing the risk of Covid-19, not only to the humans present but to Sekiu herself. As a member of the mustelid (weasel) family, she and all otters are particularly susceptible to the virus, as devastatingly shown with the recent mink infection in Europe.

So Sekiu’s procedure was assigned to the biggest health care room, and some team members – such as associate veterinarian Dr. Kadie Anderson and keeper Caryn Carter – watch from outside the door. Everyone wears N-95 masks, along with surgical caps and gloves.

On a spare table, two veterinary surgeons from partner Summit Veterinary Referral Center – Dr. E.B. Okrasinski and Dr. Brian Heiser – unpack mobile totes and begin gowning up.

“We first noticed the uterine mass during a routine annual physical exam last November,” says Dr. Wolf. “Because of its size, we knew it had to be removed.”

In the weeks leading up to her surgery, Sekiu was transported to Summit for a CT scan to confirm the precise location and extent of the tumor, and ensure it hadn’t spread to other organs.

At nine years old, Sekiu is only a middle-aged otter. Born at Seattle Aquarium, she came to Point Defiance Zoo in 2017 on a loan, and has since bonded in a happy trio with otters Libby and Moea. She’s not expected to breed, so having her uterus removed isn’t an issue. But as sea otter surgery isn’t typically needed at the Zoo, it’s a big deal for her human care team.

“We wanted to bring the surgeons here, rather than take Sekiu to Summit, so she would have minimum transit time and be able to recover outside in the cold, where she’s comfortable,” explains Dr. Anderson.

Gown tied, Dr. Okrasinski starts cutting Sekiu’s surgical drapes. Veterinary technician Sara Dunleavy adjusts an overhead light. Hands clean of goop, Lemon ties Dr. Heiser’s gown, and the surgery begins.

The first step is keeping back Sekiu’s top layer of skin, covered in the densest fur of any animal on the planet. Sea otter fur is legendary: It acts as waterproof insulation against the frigid waters they swim in, and occupies much of their time to groom. It was also their near-downfall, as humans hunted them almost to extinction for that soft, warm pelt.

Now, Dr. Okrasinski sutures sterile drapes to the furry skin to keep it out of the surgical site. An expert on dogs, cats, and an array of non-domesticated animals as well (including a ferret, muskox, clouded leopard and red wolf here at the Zoo), this is the first time he’s operated on a sea otter, and the fur is definitely a new challenge. In addition, Sekiu – like all otters – has extremely loose skin layers.

“It helps them turn right around in their skin to groom every part of their fur,” explains keeper Caryn Carter, “but it sure makes them difficult to hold onto.”

Working intently, Dr. Okrasinski and Dr. Heiser peer into Sekiu’s abdomen with high-strength headlamps. Dr. Wolf and Dr. Hadfield monitor Sekiu’s vital signs. Then –

“Here it is!” cries Dr. Okrasinski. “Wow.”

His gloved hands pull out a glistening pink mass the size of a grapefruit. There’s a collective gasp in the room. Carefully he sets it down onto a scale, where Lemon weighs it: 1.15 pounds.

It seems incredible that Sekiu had been happily swimming around with that in her uterus, but Carter nods a confirmation.

“Yes, she was eating just fine, playing with the others, very active,” Carter says.

Adds Dr. Wolf: “This is why we perform routine physical exams, because the animals often hide any signs of illness. In the wild, animals showing signs of being compromised would be vulnerable to predation.”

As the surgeons work quickly to remove Sekiu’s uterus and ovaries (which the tumor was adjacent to), Lemon returns with a large jar for the mass.

“We’ll send samples away for histopathology, and store some,” she says.

“It’s quite probably a leiomyoma, which is a smooth muscle mass that is common in the uterus of sea otters,” adds Dr. Hadfield. “We don’t know why they form, but they’re more common in older animals. It is a type of cancer but typically a benign one, where removal at surgery is the best treatment. But we’ll know exactly what kind of tumor it is after the lab results come back. The good news is that it doesn’t look to be aggressive at all.”

“Her temperature’s dropping; let’s take off the icepack,” notes Dr. Wolf.

As Dunleavy takes a blood sample for analysis, Dr. Okrasinski gives Sekiu a local anesthetic to the surgical site, which will block her pain for around three days. That’s in addition to the IV anesthetic and fluids, antibiotic, antinausea and anti-inflammatory drugs she’s been receiving during the procedure. She’ll also get oral pain medication after she wakes up, adds Dr Wolf.

Carefully, the surgeons suture up four layers of Sekiu’s skin – extra protection against water and fastidious otter grooming – and the team begins the complicated process of restoring the otter’s fur. Carter scrubs with a dry cloth in light, swift strokes, while Dunleavy grabs a hairdryer and begins thoroughly combing through the soft, black-and-white belly fur.

As the team remove Sekiu’s catheter and monitors, the surgeons pack up their totes.

“It’s so wonderful to be invited to do this,” says Dr. Okrasinski. “I feel so fortunate. When you combine our surgical expertise with that of three zoo veterinarians, I feel we do a really good job.”

Finally, Sekiu’s completely dry and ready to wake up. Carter, Dunleavy and Dr. Wolf gently scoop her up and lay her in the transfer crate. Dr. Wolf injects anesthetic reversal drugs and watches closely, ready to remove the endotracheal breathing tube as soon as she stirs.

“Sekiu!” she calls, tapping the otter’s nose to help her respond. “Wake up!”

“Hi, lady,” says Dr. Heiser, stooping to look.

Dr. Hadfield watches from the other end, calling encouragingly.

“This is such a great opportunity to see her, and be a part of her care,” she smiles.

As the sleepy otter stirs and opens her eyes, Dr. Wolf pulls out the tube and locks the door. (Otters are agile and surprisingly fierce.) Carter feeds her ice chips, and Sekiu crunches down with adorable noises. All the humans sigh appreciatively.

Then it’s time for Sekiu to go home.

“We’ll let her recover in a pool behind the scenes, then she can join the others in the larger pool,” explains Carter. “They’re very social animals, so that will help with her healing, although we’ll monitor her overnight and the next day in case they start grooming her surgical site.”

Three days later, Sekiu was back on her normal diet (except for crabs, to avoid impacting her digestion). Her fur was fluffy, and she swam and foraged with Libby and Moea in the large Rocky Shores pool. The biggest difference? She was 1.15 pounds lighter.

“I’m extremely pleased with her recovery, and anticipate she’ll do well,” summed up Dr. Wolf. “And she’ll probably feel a lot better with that tumor gone.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Great news! Sekiu’s histology results showed that the tumor was a leiomyosarcoma confined to the uterus.

“This type of tumor rarely spreads to other organs so her surgery should be curative,” said Dr. Wolf. “We will continue to check for spreading via x-rays during her routine exams, but we’re very happy about the results.”