Summer sunlight dapples through Douglas firs. The air hums with insects, pierced by sharp raven calls. All else is quiet – and keeper Jamie climbs into the truck.

Time to check up on 47 red wolves.

7:30am

Most zookeepers don’t work all alone in a forest. Jamie, however, is a staff biologist for Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium’s endangered red wolf facility, located some 35 miles from the main zoo campus at sister zoo Northwest Trek Wildlife Park. The forested facility is hidden and secluded by design: The red wolves here are part of a nationwide Species Survival Plan to save this iconic American species from extinction, and some will eventually be released into the wild, in their home range of North Carolina.

So it’s important that they stay wary of humans.

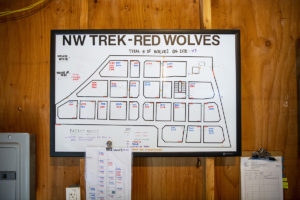

Jamie usually works with a colleague, but today it’s just her on duty. After checking into the little green office shed, plastered with whiteboards and calendars of complicated feeding plans and maps, she picks up a pail of minced meat and heads out for her first duty of the day: visually monitoring every single wolf.

“This is Sawyer and his pups from last year, with their mom,” comments Jamie, passing a family group and tossing some meatballs close to the fence. The moment they smell Jamie’s presence onsite the wolves dart to the back of the large, wooded habitat, the lanky yearling pups bounding to and fro. Eventually they approach to gobble up the meatball, and she eyes them up and down.

“This is Sawyer and his pups from last year, with their mom,” comments Jamie, passing a family group and tossing some meatballs close to the fence. The moment they smell Jamie’s presence onsite the wolves dart to the back of the large, wooded habitat, the lanky yearling pups bounding to and fro. Eventually they approach to gobble up the meatball, and she eyes them up and down.

Then she keeps going. “Here’s Jasper, and this is Juniper’s mom Juno.” An older female stands aloof, staring warily at Jamie, waiting until she’s back in the truck to get her meatball. “And Shadow, hi there, Shadow! He’s Charlotte’s son. And Wilson, hi, buddy! And our oldest wolf, Lupine. She’s 16.”

Lupine lies comfortably in dappled shade. She’s actually the oldest living red wolf anywhere, Jamie explains – a fact that’s knowable, sadly, due to the tiny population of red wolves in the U.S. – less than 20 in the wild (where they definitely wouldn’t live to be 16) and around 250 in zoos. Saved from complete extinction in the 1980s, the population is gradually being restored, thanks to a partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – and keepers like Jamie.

Jamie has worked with the Zoo’s red wolves since 2018, and it’s clear she knows every one of them. And they know her. As she goes methodically past every habitat, she gives necessary medications tucked into meat-flavored treats, her sharp eyes taking in behavior, interactions and physical condition of every wolf. Sometimes she’ll take enrichments in the form of hard-boiled eggs (laid by Zoo chickens) – a favorite treat for the wolves, which allows her an up-close visual. Often she’ll take photos to show vet staff, even taking photos through binoculars for a close view.

“We don’t want to stress them, but we also don’t want them comfortable around people, which would hurt their chances in the wild,” Jamie explains. “So we don’t often get close to them, which makes getting visuals very important.”

As she makes her way around, Jamie also stops twice to pull out an SD card from a wildlife camera strapped to a tree. Back at the office after morning rounds, she’ll go over the footage, spotting any health or behavior indications to relay to veterinary staff. In the trees nearby, the ravens comment on every move with sharp, interested cries.

“It’s pretty cool to work in a forest with ravens,” Jamie admits, “although I’m sure they annoy the wolves. They’re very loud.”

8:30am

Having given each wolf a quick check, Jamie now starts the less savory part of the day: servicing each habitat. She picks up a shovel and rake and sets off, slipping into each habitat to scoop poop.

She works silently, her footfalls almost as quiet as a wolf’s, her eyes constantly darting around her, noting the animals’ behavior and condition.

“Before this job I worked for a wildlife rehabilitation center on Bainbridge Island,” explains Jamie, who completed an Associate Degree in Zoo and Aquarium Science and six internships before getting her first zoo job in Florida. “That’s where I learned to work silently, and honed my observation skills to see subtle changes with wild animals. It has helped immensely to take care of these wolves.”

At the end of the rounds she dumps the shovel into a below-ground tank – lid carefully weighted to ward off curious ravens – washes everything thoroughly and heads back to the office. Some days she’ll work on special maintenance projects, like building platforms from fallen tree limbs which the wolves love to climb on. Other days she’ll make enrichment items for their habitats.

And just occasionally, she’ll spend the morning taking a wolf to the vet. The previous week she’d noted that Patience, a big male wolf named for his unusual disposition to hang around close to passersby in case of food, had a squint in one eye. Working from a complex plan, Jamie’s team gently maneuvered Patience into an area where he could be handled into a crate, then drove him the 35 miles to the Zoo for an exam. Under anesthetic, his eye revealed nothing worse than a hair trapped under an eyelid, but it gave veterinary staff (and Jamie) a golden opportunity to get baseline medical data, trim nails and clean teeth.

12:30pm

Jamie takes a lunch break, driving down the road to a staff house where she can check email and make coffee. She chats with other keepers in the area and savors the air conditioning on summer days – and the warmth on winter ones.

“Yes, it gets pretty cold being out there with the wolves in winter,” says Jamie. “But you just muscle on. And in the snow it’s really special, everything’s just so quiet.”

The other special experience? Hearing them howl.

“It’s really cool to hear them all howl at the same time,” she says. “I can pick out individual voices.”

1pm

Jamie finishes up any special projects, then it’s time to get lunch for her charges. From a three-door fridge inside the shed, she pulls minced meat and meat-based kibble, stacking them in the back of the truck along with a couple of massive oversized carrots.

Then she’s driving back along the fenceline, hopping out at each habitat to measure and mush up meat and kibble. Everyone gets their own amount in it’s own place – some in a communal feeding trough, some separated to make sure everyone gets some.

And as she slips inside with the food pails, she’s still watching intently, making sure everyone’s okay.

“There’s Mohe,” she says, as a big wolf slides behind the den, staring. “It’s good he’s hiding when he’s nervous, not running. In the wild that’s a good instinct for a red wolf.”

In the wild, these wolves would be eating white-tailed deer, with the occasional raccoon, nutria or opossum if they were hunting by themselves. And no, they don’t eat people – they avoid them.

“I’m a huge red wolf advocate outside of work,” says Jamie, who volunteered at Wolf Haven before getting the Point Defiance Zoo job. “I grew up in North Carolina and even I didn’t know red wolves existed until I started my studies! Now I’m the biggest fan. People don’t understand just how important they are to the ecosystem, so I like to explain that.”

Of course, there are up and down sides to any job. Jamie’s least favorite part of this one is saying goodbye as animals pass away.

“I care immensely about every single one of these animals, so that’s really difficult,” she says. “Their life span is so much shorter than ours, and you know you’ll see loss, but it doesn’t make it easier.”

The upside to that, of course, is pups, who are born in litters every year or so.

“I love their puppy smell, and watching them grow up – they’re just adorable,” smiles Jamie.

Above all, though, it’s helping save a species that Jamie loves most about this zookeeper job.

“Red wolves are like my ignition species: learning about them gave me such a drive to work with them,” she says. “I’m so glad I have this job. Helping bring back a species to the wild – that’s incredible.”