It was about as far away visually as you could get from a cute clouded leopard cub.

Scientifically, though, it was the first step of the journey.

As veterinary and keeper staff from Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium watched closely, Dr. Pierre Comizzoli from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) angled a laparoscopic camera inside Orchid the clouded leopard and gazed at her reproductive organs on the screen. Just hours before, Orchid had been given hormone injections, and if her ovaries were responding, several vials of semen from fellow Zoo clouded leopard Chee Wit were waiting in the next room.

Saving a Species

Artificial insemination (AI) in clouded leopards isn’t a new thing. Point Defiance Zoo is a founding member of the Clouded Leopard Consortium that works to protect this endangered species. As part of the consortium, the SCBI program at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. has partnered with other U.S. zoos to do successful clouded leopard AI procedures since 1992, with 17 cubs born in the last five years. It has also sent veterinary staff every year for the past seven years to consortium partner Khao Kheow Open Zoo in Thailand, training local veterinarians in AI.

Why AI? Clouded leopards, native to forests in Southeast Asia, are endangered. Their habitat is disappearing, cut down for logging and palm oil plantations; they are poached for meat and skin. Breeding clouded leopards in zoos is a crucial way to keep this species from being completely wiped out. But while natural breeding is preferred when possible, aggression can sometimes occur between males and females.

Add in zoo-raised clouded leopards who haven’t spent much time in each other’s company, and AI is the best option.

“Our clouded leopards Orchid and Chee Wit, and Sang Dao and Tien, are very good matches genetically,” explained Dr. Karen Goodrowe, Point Defiance Zoo’s general curator. “But they just don’t like being with each other physically. That’s why we’re doing AI – to try and produce healthy cubs from those pairs to keep this species’ zoo population healthy.”

A Developing Science

But although clouded leopard AI isn’t rare, it’s still a developing science. The success rate for live cubs is around 50%. Point Defiance Zoo has seen 17 cubs born since 2002 – but none were the product of AI.

“We are trying to find out why it works and why it doesn’t,” said Dr. Comizzoli, as he and fellow SCBI scientists Dr. Adrienne Crosier and Dr. Julie Lamy prepared for Orchid’s insemination. “So we study the data.”

A lot of that data lately is coming out of Point Defiance Zoo. Both Orchid and Sang Dao, a second female who underwent an AI procedure with male Tien the day before, have had their hormone levels recorded for the last 18 months through fecal sampling. Other data, such as their age (they’re both four years old, born here in May 2015), genetics (all nine of the Point Defiance leopards are tracked in the Association of Zoos and Aquarium’s clouded leopard Species Survival Plan®, or SSP) and reproductive history (Orchid has been on birth control, Sang Dao hasn’t) are part of the database.

“We’re trying to better understand the species’ biology,” explains Dr. Crosier. “And we’re learning a lot.”

Timing is Everything

So how does AI work in clouded leopards?

First, a genetically compatible male and female are selected through the SSP. The female is monitored, and at the right time in her hormonal cycle she’s given two injections of a reproductive hormone to trigger her ovaries to produce mature eggs. Semen is collected from the male and stored at room temperature in a special solution to ensure its viability.

Soon after, under anesthesia, a laparoscopic camera is inserted into the female’s abdomen to see if her body has responded to the hormones – dark red dots become visible on the surface of her ovaries as a sign of ovulation. If that happens, a second tube is snaked up from the laparoscopy site and the semen gently injected into the female clouded leopard’s oviduct (or Fallopian tube).

If the female doesn’t respond to the hormones, the semen can be frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored indefinitely for future use. The first clouded leopard cub ever produced from AI using cryopreserved semen was born in 2017 at the Nashville Zoo – another partnership with the SCBI.

Orchid and Chee Wit

Now Orchid lay, furry abdomen shaved, on a table in the Point Defiance Zoo’s animal hospital. Zoo veterinarian Dr. Kadie Anderson had prepped and anesthetized her, and Drs Crosier and Comizzoli had surrounded her abdomen with sterile drape and gently inflated it to visualize the organs. Now, veterinary technician Julie Lemon tilted the table so Orchid’s intestines would not get in the way, and Dr. Comizzoli inserted the laparoscopic camera.

All eyes were on the screen as the camera swam down past Orchid’s bladder to her ovaries.

No red dots.

Dr. Comizzoli sighed. “Okay, that’s it, time to pack up,” he said. No response to the hormones, no need for AI.

Dr. Anderson and assistant curator Maureen O’Keefe gently lifted Orchid to another table, where she’d get a wellness check-up before waking up.

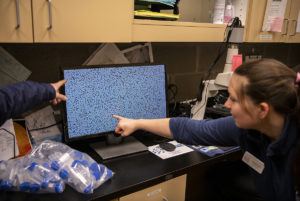

Next door, Dr. Lamy began transferring semen into straws. A tiny drop sat on a slide under the microscope, filling the screen nearby with thousands of swimming tadpole-like dots of sperm. Later, Dr. Goodrowe would tip some liquid nitrogen from a heavy tank into a cooler, vapor clouds swirling, and gradually lower the straws until they were frozen and ready for transport to the SCBI cryobank.

Meanwhile, the science was just beginning. Orchid’s data would go into the study, along with that of Sang Dao, who would have fecal hormones continually tested until pregnancy could be confirmed or ruled out in several months’ time. Maybe there would be cubs – or maybe not. Either way, there would be another drop of scientific knowledge for clouded leopard AI.

“We’re increasing knowledge about reproduction in this species,” summed up Dr. Crosier. “The more we do this, the more we learn how to keep the clouded leopard population healthy.”

And in her comfy recovery crate, Orchid was slowly opening her eyes and stretching. A healthy clouded leopard, helping to keep her species alive.